GAO Puts the NCUA on Report: The Questions You Need Answered

While many a credit union leader may have smirked when the Government Accountability Office slapped the NCUA on the wrist for steps it deems necessary for effective oversight of credit unions, be mindful, particularly as credit unions’ CAMEL (soon to be CAMELS) ratings decline and depending on which element falls. The GAO wrote:

Specifically, the likelihood of a CAMEL composite rating downgrade from a 2 to a 3 at the next examination increased by 72 percent (over a baseline risk of 10 percent) if the Asset component was rated a 3, or by 21 percent if the Liquidity component was rated a 3. Furthermore, the likelihood of a credit union with a CAMEL composite rating 2 receiving a downgrade to a 4 or 5 by the next examination increased by 20–90 percent—depending on the component—if one of the components (except Liquidity) was rated a 3, from a baseline risk of 0.8 percent.

Who’s at Fault When a Credit Union Fails?

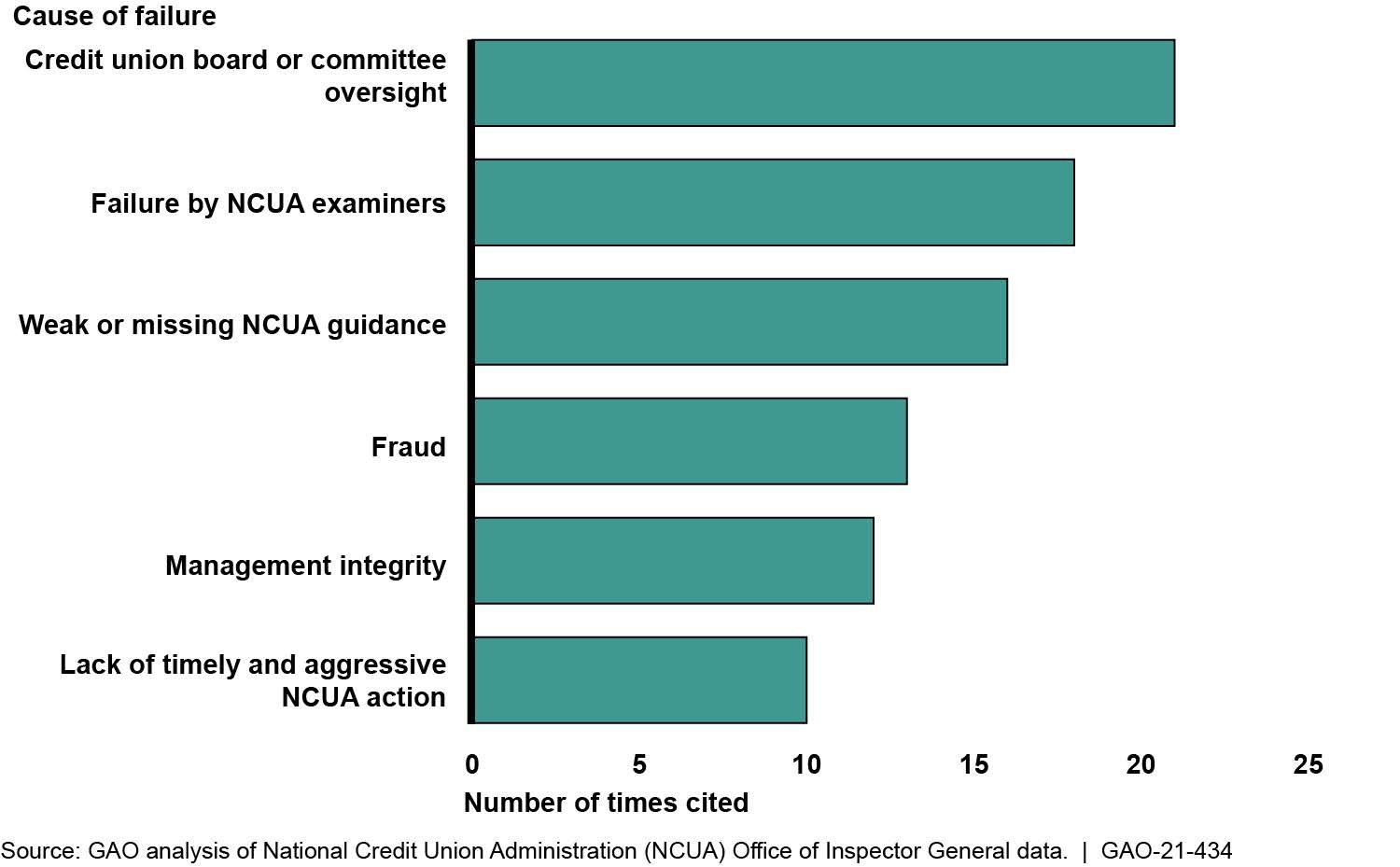

The most common failure of oversight, according to the NCUA’s Office of Inspector General lands squarely on credit union board and committees. I am a credit union board member, and this is a systemic issue that must be taken very seriously for the reputation of individual credit unions, as well as the entire credit union community.

Our volunteer boards of directors and others are credit unions’ greatest strength and worst enemy. Very frequently, our credit union boards represent our membership well and with their interests top of mind. But volunteering for a credit union board is much more than that. This isn’t like reading appropriate materials to kids at the local library. Volunteering for a credit union requires a lot of consistent hard work, constant education and understanding of many different aspects of the business.

Top Material Loss Review Causes or Contributors to Failure by Number of Times Cited, 2010–2020

Some credit union volunteers don’t take that responsibility seriously enough. I can’t count the number of times I’ve heard, ‘but they’re just volunteers.’ Does that make the fiduciary duties any less important than if you were paid for keeping the financial institution? NO.

We owe it to our members and the cooperative credit union community to 1) recognize when we need to leave our board positions because we’re not able to perform the necessary tasks, 2) speak up when we know that others are not upholding their obligations and ask them to step down, and 3) regularly recruit for new volunteers to serve on committees, advisory boards and as associate volunteers, so we have people ready to step in as others need to step out. The buck stops with us.

Many of the failed credit unions tend to be smaller ones that don’t cause massive material losses to the National Credit Union Share Insurance Fund. However, the GAO was split on who owns the blame for the credit unions that fail big.

Specifically, OIG-identified causes of failure associated with the largest total losses to the NCUSIF were insufficient credit union board or committee oversight ($1.4 billion in 2020 inflation-adjusted dollars), lack of timely and aggressive NCUA action ($1.3 billion in 2020 dollars), credit union lending practices ($1.2 billion in 2020 dollars), credit union risk-management practices ($1.1 billion in 2020 dollars), credit union loan portfolio concentration ($1 billion in 2020 dollars), and weak or missing NCUA guidance ($1 billion in 2020 dollars).

Volunteers, management and the NCUA were all at fault, according to the GAO, and we’ve all heard each point fingers at the others. Just read the NCUA’s response from the GAO report.

NCUA required this or didn’t allow that; management refused to do this or that. In the end, everyone is to blame. Let’s accept and fix these problems because no one will like what comes next.

Who’s Going to Pay for This?

The GAO’s report is clear:

[T]he NCUA OIG commonly cited weaknesses or failures in NCUA oversight as one of the causes for credit union failures; these failures impose losses on the NCUSIF, which insures members’ accounts and is backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government. NCUA also identified emerging risks for credit unions during the COVID-19 pandemic. These weaknesses and emerging risks illustrate the importance of NCUA improving its oversight of credit unions.

The NCUA, which is funded entirely by the credit unions it regulates and insures through the NCUSIF, is going to pay for it, so that means credit unions – literally and figuratively. The 3 recommendations that came from the GAO to the NCUA (leveraging oversight via CAMELS; incorporating modern risk identification tools; and adding post-mortem oversight processes and procedures) will all take time and money from the agency (aka credit unions). What the agency does with these tools will take additional time and money from credit unions that will not be able to reinvest in serving their members.

Who Are the Winners and Losers?

If we, the credit union community collectively, doesn’t button down these fundamental issues of strategic planning completed in good faith, doing the real work to strengthen the industry, shore up regulatory and volunteer board oversight, the real losers will be our members. American consumers have relied on credit unions as the ones looking out for them in a way no other financial institution can. Credit unions are special and unique. We work with members when others won’t.

Even for those who choose other financial options benefit from the marketplace pricing pressures credit unions put on other lenders. The credit union tax exemption is a rare and successful public-private partnership that has been successful for more than a century. We all have too much riding on this.

Credit unions are going to lose time and money with additional oversight coming from the NCUA. Regulators serve a reasonable purpose when they’re reasonable, like adding the aforementioned S to CAMELS for consistency with the other banking regulators and greater transparency. The agency also recently passed a rule to expand CUSO authorities, over the objections of Chairman Harper, so they can better help credit unions compete.

He and consumer advocates argued that allowing CUSOs too much authority can lead to sidestepping consumer protections and financial ruin of not only the CUSO, but also its credit union owners, without NCUA oversight. CUSO fraud and failure has happened a few times in the past, but hundreds if not thousands of CUSOs exist today that are not out to screw American consumers. Anything is possible, but as responsible, ethical businesspeople including regulators, credit union board members and CEOs, we should keep our focus on what’s probable. And credit union leaders who serve on CUSO boards must keep the mission and uniqueness of credit unions in mind, because no one will like what comes next.

Does Any of This Matter? You tell me!